KEET

www.biancaanddaniel.com

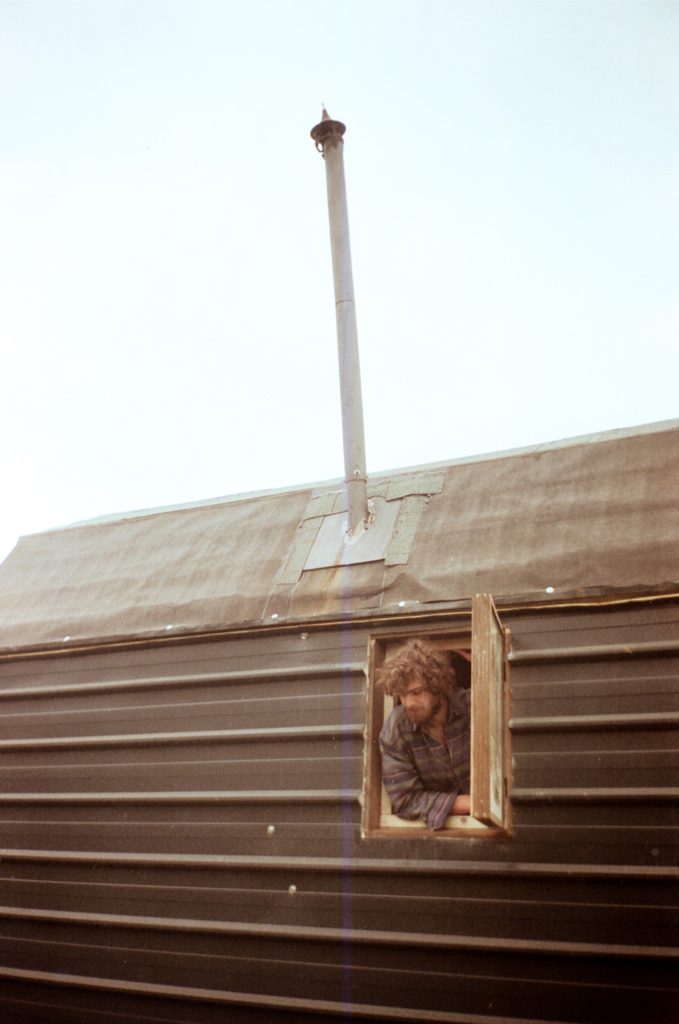

Keet started to take shape in June 2013.

It is now located in Gent (Belgium), at Tuin van Heden, a social and cultural non-profit organisation in the neighbourhood of Ledeberg.

The past locations of the keet are: KASK, the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Sprundelsebaan 60, a squatted historical monument farm in Breda (The NL), a small plot of forest in Etten-Leur (The NL), Simon and Sanne’s farm in Galder (The NL), the Verbeke Foundation, a private art museum in Kemzeke (Belgium) and DOK, the temporary occupation and revival of a post-industrial terrain, which accommodates social, cultural, art, ecology, sport and well-being initiatives in Gent (Belgium).

When moving, the keet is pulled by a tractor at 20-30 km/hour.

Goal

Keet wishes to be accepted and spread as a guide and alternative to the standard model of living/housing.

The environmental, financial, practical and autonomy talk

As a reaction to the standards, myths (the harder you work, the more stuff you can buy, and the bigger house you can afford to fit it all in) and comforts (central heating, hot showers, science-fiction kitchens etc.) prevalent in the capitalist society, we try to rethink, redesign, rebuild and replace all taken for granted basic need structures (sleep, eat, shower etc.) in a single unity, the keet.

In winter for example, instead of simply setting the central heating at a high temperature, we need to look for (scrap) wood to burn.

Other examples would be collecting rain water for showering, clothing and dishwashing, the use of waste materials itself, the preference of mechanical over automatic appliances and of hand-driven tools over power tools, the use of solar panels, converting all electric equipment to 12V for an off-grid situation, but also keeping an inter-disciplinary circle of friends.

When living in a tiny space, you are very aware of how much stuff you gather (the objects inside the house are mostly objects we make use of regularly), what and how much you consume, what waste you produce. [3]

The mobility aspect makes sure that regardless of not yet owing land/ property we are still able to seek for places where to park (‘Home is where you park it’).

The choice to use waste materials, is not only environmentally friendly, but also financially. The building costs of the keet are marginal (around 500 euros).

We believe tiny, mobile living is an appropriate formula for living practically, autonomously, being environmentally responsible and financially independent in the present-day.

[3] Because garbage is the main source of sustaining ourselves, it is an exceptional situation, in which there are less guilt feelings involved regarding the produced waste, as it was already waste to start with.

(scrap food though is either used as compost or to feed the chickens)

How the rest of the world perceives it

Keet is often associated with caravans, either with the traditional gypsy caravan, the 60’s hippie van or with the retired people holiday caravan. Though it was inspired by none, they do share the dimensions (fit for the road), the mobility aspect, the function- (temporary) home and arguably, the looks.

But again, keet has taken this shape not because ethnicity, counter-culture or recreational reasons, but because of environmental, economical, autonomy and practical concerns, in accordance with the current social and political context .

As mentioned in the brief introduction, the keet has changed several locations.

In the first months of building, it was placed on a squat farm, then on a small plot of forest, then on a farm of two friends in Galder, together with other similar ‘housing’ projects. [4]

Because of legal difficulties, we then chose to live at the Verbeke Foundation, a private art museum spread on 12 ha.

If living and building on a squatted terrain would be looked down upon by the conservative public of Breda, in contrast, in the backyard of an art museum, the keet would symbolize freedom , nature, simplicity and other similar ideals. Visitors would assume we are artists, and the keet is art, would take pictures of our laundry, flower pots, power tools etc. and ask at the reception about the possibility to rent it during weekends.

In its latest context, at DOK, we are happy to observe the keet is perceived close to its original intentions. ‘Yay recycle’ Gent is very welcoming and supportive.

Maybe the most animosity and suspicious reactions towards the keet come from the laziness prejudice (e.g. “You get things for free”, “You don’t contribute to society”, “How do you make money?!”). This condescending attitude stems in the misconception that functioning outside wage-labour structures is impossible and morally questionable.

It is easy to argue that gathering and reusing garbage contributes more to society and environment than collecting and throwing away do. [5]

Another ideology surrounding the keet is the ´simple living´: a pure and honest return to the times when people were living in harmony with nature. Again, the intention is not to lack comforts, but to rethink them. The WIFI (lady at the internet provider company made us look for for a telephone connection inside our house; we couldn’t find it) and the hair-dryer are giving the most trouble.

[4] Choosing to live in a keet (tiny, mobile house) is rather common in the squatting scene, especially since squatting is less and less tolerated, and buildings get evicted very soon after being squatted. Instead of investing time to set all the facilities in a newly squatted place, (kitchen, shower, sleeping places etc) which would probably get evicted within two weeks or one month, the idea is to concentrate all the basic facilities in a space which is easy transportable to the next (squatted) place.

[5] It is relevant to also mention skipping (dumpster diving) for food.

Skipping is a similar activity to shopping: you go to the supermarket to get food.

Shopping involves long thinking upon what food (or toothpaste, toilet paper, shampoo…) to pick and then picking it from the abundant and neatly organized shelves, while your ears are being raped by cheesy music.

But supermarkets don’t only sell food (2/3), they also throw away food (1/3).

Skipping involves cycling around, trying to spot supermarket containers which are easy to reach. These days most of the supermarkets either keep their containers inside, build fortresses around them or pour chemical substances like bleach on the products inside, making it impossible to reach/eat/use. But if you are lucky and find a plentiful container (bread, cheese, meat, milk products etc.), then the repetitive activity of getting food from the supermarket, is undoubtedly more adventurous and rewarding (both personally and environmentally) if skipping rather than shopping.

Inside description

Keet contains: a double-bed, a bed for the dog, clothes drawers, a source of heat (wood burning stove), a desk and shelves for administration, book shelves, a piano keyboard, a cabinet for shoes, a couch/ bed for guests with various compartments for storage (wood, blankets, jars etc.), a knitting corner, a sewing machine, a bee-keeping corner, a kitchen (including an oven which works on gas and a fridge), a shower, a sink, a small washing machine, storage space.

The main challenge is to fit in ergonomically all our personal belongings. We therefore built many closed or hidden drawers and compartments, and also objects with double or triple function.

Outside description

On the outside there is a small porch and a balcony.

As an extension to the keet, there are also a bakbrommer (a cargo scooter) which is used to collect building materials, a shed for tools, storage for materials, a plateau for plants (flowers, spices, vegetables), two bee hives and a wooden fence surrounding the chicken and goat area.

All these outdoor structures are easy to take apart, put on a flat trailer, transport and rebuild in other locations.

While the interior remains the same, the outside view and possibilities are changing with the location.

Materials

We believe creativity grows out of limited resources (the use of local/ recycled materials) rather than abundance. In the building process, we first consider the given need (for example the need of a shower or a chair), then the available materials, and only last, the solution. The ‘material prior to idea’ approach makes for us more sense sustainably than the common ‘idea-choice of material’ sequence driven by consumerism. [1]

The inverted design process makes the keet impossible to reproduce. There cannot be a second or a third keet, as would be the case if the materials were to be bought in the building shop.

The construction materials we buy second-hand if they are impossible to find for free (e.g. solar panels, sandwich panels, steel from the scrap yard), but mainly we have used garbage, the new vernacular [2], which we separated in two categories:

A. materials we know that are in the containers and we can count on them being there:

pallet wood from containers on industrial grounds

doors and windows from building containers outside houses which are being renovated/ demolished

scrap wood (beams, planks, plates) from industrial or building sites waste

glass wool insulation etc.

B. materials we randomly find on the street/containers (our oven, fridge, stove, mattress etc.)

Of course, when using unwanted materials, there is the added element of surprise (the unknown) which we enjoy. Most of the everyday experiences are expected: going to school/work, taking the train/tram, the walk to the supermarket…Even when going on holidays you already know what you are going to see/consume/experience: the Eiffel Tower, croissants, tanned Italians etc. The inside of a container though is one of the few things that can provoke curiosity and excitement (‘What will I find there?’).

[1] The only negative aspect of this approach is the difficulty/impossibility to store all the materials found and decide upon what is useful to keep for later on. City containers are without doubt generous and reliable on a constant basis, but we find it important not to simply seek and collect, but also to be able to make good selections and have good organizing systems.

[2] Vernacular architecture uses building materials that are both local, plentiful and for free (or very cheap) in an area; for example stone houses in rocky areas, wooden houses in Scandinavia, igloos in Antarctica etc. In (big) cities though, the only free and locally available material is garbage, therefore garbage can be declared the new vernacular.

Technical details:

Dimensions: 6m length by 2,5m wide and 3,97m high (the maximum height permitted on the road is 4m high)

All triangles in the frame construction are “Thales Triangles” (or 30-60-90 Triangles); apart from them being visually pleasing, they also allow for easy calculation, as the ratio between the hypotenuse and 60-90 leg measures exactly 2:1.

The basic steel frame, that comes from an old flat agricultural chart, was reinforced with some L-profiles.

Little plates were welded in U-profiles, so they could be connected with bolts; they were cut so they could support the walls and the gambrel roof, and can be possibly reused to form the frame for another structure.

Sandwich panels were bolted to the frame; again it is perfectly possible to reuse the panels in a different configuration, if wished so.

Flooring consists of a layer of plating, then a wooden frame insulated with glass wool insulation; the top layer consists of second planks.

Windows and doors were placed in scrap wood posts, in wooden frames extending from the steel base-frame.

For the roofing material we have used bitumen.

Discussion KEET